While the title of this post is a bit over-dramatic, for me, it is truly the end of an era. Today is my last day working as a researcher in experimental cosmology and I’ve been involved in this research for the better part of 15 years.

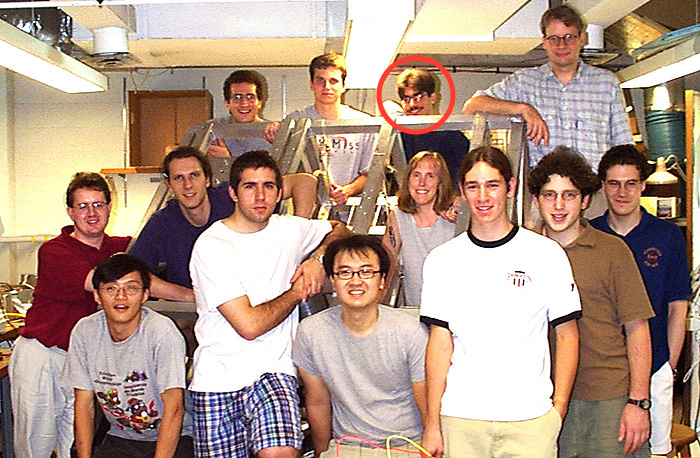

I got my start in physics in a slightly non-traditional way. I wasn’t one of those kids that dreamed about space or the mysteries of the universe from a young age and I wasn’t particularly engaged in science classes either. Instead, I was a long-haired emo high school junior more interested in literature and philosophy who ended up interested in physics because it provided definitive answers to questions I found interesting then. I stumbled into experimental research as an undergraduate by walking into one of the labs that was known to hire undergraduates for the summer and asking for a job. It turned out I was fast with a soldering iron, good in the machine shop, and quick to figure things out in the lab, so I kept getting hired back each summer. I worked in Lyman Page’s lab every summer of my undergraduate career and it was a blast. Below is a photo of the summer crew from 2002 working on the MINT experiment. MINT deployed to Chile steps from where my thesis experiment POLARBEAR ended up being fielded.

Aside from Lyman (to my left) and Suzanne Staggs (directly below me), the two Princeton professors I worked with on the project, I got to know Huan Tran (the guy with glasses in the front) very well by helping him take some data that characterized a component of the experiment he built for his graduate thesis. I ended up a graduate student at Berkeley where he had started as a postdoctoral researcher and we worked together for most of my time there. Unfortunately, he suffered a tragic accident and died from carbon monoxide poisoning at a hotel while working on POLARBEAR during our initial deployment in the Eastern Sierras. I often wonder about the conversations we would have had if he were still alive and gotten to see POLARBEAR turn into a successfully deployed experiment and where the field is today. I’m sure we would have had an interesting conversation about my decision to leave the field at this point.

So back to the topic at hand; after working in Lyman’s lab on experimental cosmology for those summers, seeing how small teams of graduate students, professors, postdocs and undergraduates built amazing instruments and analyzed the resulting data to extract information about the fundamental nature of our cosmos, I was pretty hooked. I still remember how excited my classmates and I were when Lyman showed us what would become the plot of the angular power spectrum from the first release of WMAP data over pizza and soda. Thinking I could someday help build an instrument that went even deeper into measuring this amazing remnant from the big bang was awe-inspiring. The pizza was also pretty great (sidenote: as an undergraduate, I was able to down an entire sausage and cheese pie from Old World Pizza all by myself).

So why leave? I was lucky enough to have opportunities to continue with my research, at least in the near term. And my particular field is entering an exciting phase where we’re beginning to make measurements that put interesting constraints on fundamental physics occurring in the very early universe. Unfortunately, academia is not the place to be if you’re interested in choosing where you live or having stability for timescales greater than “the near term” of 4-5 years (unless you’re lucky enough to be bestowed tenure). I’ve enjoyed living in New York City tremendously over the past three years, despite the often horrible commute. When I took the time to think about the balance between work and family life, I simply found it difficult to imagine myself and my family being happier with our home and city than we are with New York, but I can think of many alternative careers paths that would make me as happy as research has (and maybe even happier?).

In exploring careers outside of academia, I’ve always been drawn to tech and the startup culture. I feel there are a lot of parallels to the core aspect of research I love: small teams of clever folks scrappily finding the quickest solution to ever-evolving problems. The burgeoning field of data science is a particularly good fit as it builds on a lot of the skills I already have and seems to value physicists like myself who are used to dealing with open-ended, ill-defined problems and gleaning insights from large, noisy data sets. So I applied to and was accepted to the Insight Data Science fellowship. The program works with quantitative PhDs from a variety of fields and prepares them for data science jobs in industry, helping them find jobs at the end of the program. They’ve been operating out of the Bay Area for several years now and have had several sessions in New York, where I’ll be doing the program. I’m incredibly excited about the program and the prospects for my future career. The program starts in September and until then, I’ll be spending all of August as a stay-at-home dad for my son Otis. Expect a blog post or two about that.

The last few months working at Princeton have provided a surprisingly fitting amount of closure as I move on to other things. SPIDER had a full collaboration meeting to discuss the ongoing data analysis and some of my more senior and distinguished colleagues at Princeton organized a celebration in honor of the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the CMB. The conference was an interesting set of talks focusing on the history of measurements in the field and musing over exciting new measurements to come in the near future. It also served as a reunion for the many players in the field. For me, it was bittersweet catching up with collaborators I’ve worked with over the years on both POLARBEAR and SPIDER and discussing my future plans to switch gears.

The photo below is the group picture we took at the conference. I’m somewhere in the center left section of the group. I’ve had the pleasure of working closely with many people in this photo, learning from their vast experience and collective knowledge. Many thanks to all my mentors and colleagues for their support over the years.

I’m looking forward to what’s next but I will miss building microwave telescopes and traveling all over the world to deploy them. I’ll save those stories for Otis.